Ever caught yourself peering into the mirror, only to realize your head is leading the way, like a curious turtle inching out of its shell?

You’re not alone.

This common stance, known as Forward Head Posture (FHP), has become as ubiquitous as smartphones and binge-worthy TV series.

But while modern habits like excessive screen time and poor posture often take the blame, could our genes be the silent puppeteers pulling the strings?

BestForwardHeadPostureFix research suggests that genetic factors play a significant role in FHP. Some individuals are born with naturally shorter neck muscles or variations in cervical spine structure, which predispose them to a forward-leaning head position.

Conditions like Klippel-Feil Syndrome, which fuses cervical vertebrae, or congenital torticollis, which shortens one side of the neck, can make proper head alignment a challenge from birth.

So, while lifestyle choices do matter, your DNA might have set the stage for your posture long before you ever picked up a smartphone.

Article Index:

- Understanding Forward Head Posture (FHP)

- The Genetic Link: Short Neck Muscles and FHP

- Klippel-Feil Syndrome: A Genetic Culprit

- Torticollis: When Neck Muscles Take a Twist

- The Domino Effect: Consequences of FHP

- Corrective Measures: Exercises and Interventions

- FAQs on Genetically Short Neck Muscles & Forward Head

- Conclusion: Embracing Our Genetic Blueprint While Standing Tall

Understanding Forward Head Posture (FHP)

Forward Head Posture (FHP) occurs when your noggin decides to take a mini-vacation ahead of your shoulders, positioning itself in front of your body’s vertical midline.

In an ideal world, your ears should align gracefully with your shoulders, like soldiers in a perfectly executed drill.

But with FHP, this harmony is disrupted, leading to potential neck pain, stiffness, and an uncanny resemblance to a question mark.

Imagine holding a bowling ball close to your chest—it feels manageable. Now, extend your arms and hold the ball forward.

Suddenly, the weight feels heavier, and your arms strain to keep it up. Your head, weighing about 10-12 pounds, works the same way.

When positioned correctly, the neck muscles bear its weight efficiently. But if it leans forward, the strain multiplies, forcing muscles and vertebrae to work overtime.

Over time, this leads to muscle imbalances, chronic pain, and even changes in spinal curvature.

The Genetic Link: Short Neck Muscles and FHP

While modern habits like prolonged screen time and poor posture are often blamed for Forward Head Posture (FHP), genetic factors can also play a significant role.

Certain congenital conditions lead to shortened neck muscles, predisposing individuals to FHP.

Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT):

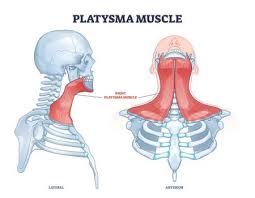

This condition manifests when an infant’s sternocleidomastoid muscle—a key muscle facilitating head movement—is shortened or tightened at birth.

As a result, the infant’s head tilts to one side, and the chin points to the opposite direction. If untreated, this muscle imbalance can lead to FHP as the body compensates for the altered head position.

According to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (chop.edu), early intervention through physical therapy can significantly improve mobility and reduce postural imbalances.

Klippel-Feil Syndrome (KFS):

KFS is characterized by the fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae, leading to a shortened neck and restricted mobility.

This structural anomaly can cause the head to lean forward, contributing to FHP. Individuals with KFS often present with a low hairline and limited neck movement, making them more susceptible to developing FHP.

The National Library of Medicine (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) explains that this syndrome often requires specialized treatment, including posture correction and physical therapy.

Genetic Predisposition:

Beyond specific syndromes, studies have shown that genetic factors can influence neck pain and posture.

Research published in the National Institutes of Health’s Public Medical Central (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) indicates that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of neck pain, which is often associated with FHP.

Understanding these genetic links underscores the importance of early detection and intervention.

For instance, infants diagnosed with CMT can benefit from physical therapy to stretch and strengthen neck muscles, potentially preventing the progression to FHP. Similarly, individuals with KFS should be monitored for postural deviations to implement corrective measures promptly.

In conclusion, while lifestyle choices undeniably impact posture, genetic factors can predispose individuals to FHP. Recognizing these underlying causes is crucial for effective prevention and management strategies.

Klippel-Feil Syndrome: A Genetic Culprit

Klippel-Feil Syndrome (KFS) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by the fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae, leading to a shortened neck and limited mobility.

This fusion results from a failure in the normal segmentation of the cervical vertebrae during early fetal development, as explained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Clinical Features:

- Short Neck: The reduced number of cervical vertebrae leads to a visibly shortened neck.

- Low Hairline: Individuals often exhibit a low posterior hairline due to the shortened cervical spine.

- Limited Neck Mobility: The fusion restricts neck movement, making actions like turning the head challenging.

Associated Complications:

Beyond the primary triad of symptoms, KFS can be associated with various other anomalies:

- Neurological Issues: The fusion can lead to spinal stenosis, increasing the risk of nerve compression and neurological deficits.

- Musculoskeletal Abnormalities: Conditions such as scoliosis (sideways curvature of the spine) and Sprengel’s deformity (elevated shoulder blade) are commonly associated with KFS, as noted by Boston Children’s Hospital (childrenshospital.org).

- Organ Malformations: Some individuals may have congenital heart defects, kidney anomalies, or hearing impairments, according to MedlinePlus (medlineplus.gov).

Diagnosis and Management:

Early diagnosis is crucial for effective management. Diagnostic approaches include:

- Imaging Studies: X-rays, MRI, or CT scans assess the extent of vertebral fusion and detect associated anomalies.

- Physical Examination: Evaluating the range of motion, neurological function, and identifying any associated anomalies.

Management strategies focus on alleviating symptoms and preventing complications:

- Physical Therapy: Helps maintain and improve neck mobility and strengthen supporting musculature.

- Surgical Intervention: In cases with significant neurological involvement or severe deformities, surgical options like decompression or spinal fusion may be considered.

Understanding KFS’s implications is vital for healthcare providers to ensure timely interventions, improve quality of life, and address potential complications effectively.

Torticollis: When Neck Muscles Take a Twist

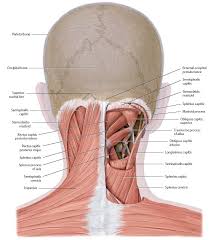

Torticollis, commonly referred to as “wryneck,” is a condition where the head tilts due to involuntary muscle contractions, primarily affecting the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

This muscle, extending from the sternum and clavicle to the mastoid process behind the ear, plays a pivotal role in head movement.

When it becomes shortened or tight, it can pull the head into a forward and rotated position, potentially leading to Forward Head Posture (FHP).

Types and Causes of Torticollis:

There are two types of Torticollis. A quick look at both these in brief:

Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT):

Present at birth, CMT often results from the infant’s position in the womb or birth trauma, leading to a shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle.

This shortening causes the head to tilt toward the affected side and the chin to point to the opposite side. If left untreated, CMT can result in asymmetrical facial development and FHP.

As per the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (chop.edu), early intervention with physical therapy can improve muscle flexibility and prevent complications.

Acquired Torticollis:

This form develops due to various factors, including:

- Trauma or Injury: Sudden movements or accidents can cause muscle spasms in the neck, leading to torticollis.

- Infections: Upper respiratory or ear infections can irritate neck muscles, resulting in spasms.

- Neurological Conditions: Disorders affecting the central nervous system, such as Parkinson’s disease, can manifest with torticollis symptoms.

- Medications: Certain drugs, particularly antipsychotics, can induce dystonic reactions, causing muscle contractions in the neck, as noted by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (ninds.nih.gov).

Impact on Posture:

The abnormal positioning of the head in torticollis alters the alignment of the cervical spine. This misalignment increases strain on neck muscles and ligaments, potentially leading to FHP.

Over time, the body may adapt to this altered posture, resulting in muscle imbalances and chronic pain, as explained by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (orthoinfo.aaos.org).

Symptoms Associated with Torticollis:

- Neck Pain and Stiffness: Muscle tightness can cause discomfort and limit range of motion.

- Headaches: Tension in neck muscles can radiate to the head, leading to tension headaches.

- Shoulder Elevation: One shoulder may appear higher due to muscle imbalances.

- Tremors: Some individuals experience shaking or tremors in the head.

Treatment Approaches:

- Physical Therapy: Stretching and strengthening exercises can improve muscle flexibility and correct posture.

- Medications: Muscle relaxants or anti-inflammatory drugs can alleviate pain and reduce muscle spasms, as recommended by Mayo Clinic (mayoclinic.org).

- Botulinum Toxin Injections: These injections can temporarily paralyze overactive muscles, providing relief from spasms.

- Surgical Intervention: In severe or refractory cases, surgical procedures may be considered to release tight muscles or correct anatomical abnormalities, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine (hopkinsmedicine.org).

Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial to prevent long-term complications associated with torticollis and its contribution to FHP.

A multidisciplinary approach, involving healthcare professionals such as neurologists, physical therapists, and orthopedic specialists, ensures comprehensive management tailored to the individual’s needs.

The Domino Effect: Consequences of FHP

Allowing your head to lead the charge is not just a cosmetic concern—it is a biomechanical imbalance that can have serious consequences.

Forward Head Posture (FHP) shifts the head’s weight forward, forcing the neck and upper back muscles to compensate for the added strain.

This increased workload can cause some muscles, like the upper trapezius and levator scapulae, to become overactive and tight, while others, like the deep cervical flexors, weaken due to disuse.

Over time, this imbalance contributes to chronic neck pain, stiffness, and tension headaches caused by excessive strain on the cervical spine.

According to Spine-Health (spine-health.com), FHP can also affect breathing by compressing the airway and reducing lung capacity, making it harder to take deep breaths. Additionally, poor head positioning can alter balance and increase the risk of dizziness.

Left uncorrected, these issues can contribute to long-term postural dysfunction, requiring physical therapy and lifestyle changes to reverse.

Corrective Measures: Exercises and Interventions

While we can’t rewrite our genetic code (yet), we can take proactive steps to counteract its effects and improve posture. One of the most effective exercises is chin tucks, which help strengthen the deep cervical flexors.

These muscles are essential for maintaining proper head alignment and reducing forward head posture (FHP). As per Health.com, performing chin tucks regularly can retrain the neck muscles to support the head in a more neutral position.

Chest stretches are another crucial tool in combating FHP. Since tight chest muscles can pull the shoulders and head forward, stretching them helps open the upper body, allowing for a more natural posture. Health.com suggests incorporating stretches like the doorway stretch to release tension and restore muscle balance.

Additionally, ergonomic adjustments can make a huge difference. Raising computer screens to eye level, using supportive chairs, and maintaining proper desk posture help reduce strain on the neck and prevent the progression of FHP.

FAQs on Genetically Short Neck Muscles & Forward Head

A few people are simply built a bit tighter through the neck—thanks, genetics—and that can set the stage for a head-forward look.

The good news: even if you drew the short straw on muscle length, smart training can still bring your head back home.

Q-1. Can genetics really make neck muscles “short,” nudging the head forward?

A-1. Yes. Flexibility and muscle-tendon properties vary from person to person, and some of us inherit stiffer or shorter tissues. That baseline tightness can bias posture under daily loads—especially with screens and sports—making a forward head position more likely unless you actively counter it.

Q-2. Which conditions link short or tight neck tissues to altered head position?

A-2. Congenital muscular torticollis can shorten the sternocleidomastoid, pulling the head into tilt/rotation and compensatory forward carriage. Rare skeletal variants, like fused upper cervical vertebrae, create a “short neck” with limited motion, encouraging a chin-forward strategy to keep eyes level. These need clinical assessment to confirm and guide care.

Q-3. Mechanically, how do short/stiff tissues create forward head posture (FHP)?

A-3. When upper-cervical extension is restricted, your body cheats: it projects the head forward to maintain vision and airway space. Each extra degree increases the load on the neck; around 60° of flexion, the cervical spine can experience forces comparable to roughly 60 lb—so small inherited limits can snowball under modern habits.

Q-4. How do I know if my FHP is more “genetic” than habit?

A-4. Clues include early-life onset, family resemblance (short necks or similar posture), and stubborn range-of-motion caps despite good ergonomics. A clinician can screen for congenital patterns, check muscle length and joint mobility, and rule out other drivers (nerve irritation, joint degeneration) before prescribing targeted rehab.

Q-5. What actually helps if I’m predisposed?

A-5. Evidence-based rehab still wins: deep cervical flexor activation, scapulothoracic strengthening (lower traps, serratus), and thoracic mobility drills. Progress gradually—Isometrics → endurance holds → dynamic strength—and pair it with ergonomics (eye-level screens, timed breaks), sleep alignment (back/side with supportive pillow), and breathing work. Genetics set the baseline; training sets the trajectory.

Embracing Our Genetic Blueprint While Standing Tall

Our genes may set the stage, but we are the directors of our postural play.

While genetic factors like shortened neck muscles or congenital conditions may predispose us to Forward Head Posture (FHP), they do not determine our destiny.

Understanding these inherited traits empowers us to take control—through targeted exercises, mindful posture habits, and ergonomic adjustments, we can counteract the effects of FHP and reclaim a more balanced, pain-free posture using posture correction techniques.

Posture is more than just a physical stance; it reflects confidence, health, and well-being.

By actively engaging in corrective measures, we can reshape the way we move through the world—standing taller, breathing better, and reducing strain on our bodies.

So, let’s take charge of our posture, not just to defy gravity, but to embrace the strength and uniqueness of our genetic blueprint.

After all, the best way to honor our genes is to rise above their limitations—literally and figuratively.

References: