Ever caught your reflection hunched over a screen, chin jutting forward like a turtle on a mission?

That is forward head posture—what many call “text neck” or “tech neck.”

It may start as a harmless slouch, but over time, this posture transforms into a full-blown upper back pain generator.

What’s interesting (and slightly alarming) is how a simple tilt of the head throws the entire upper back into a war it didn’t sign up for.

BestForwardHeadPostureFix research team shall break down the science behind it.

Why does forward head posture cause your upper back to tighten like a rusty hinge?

And how exactly do muscles, joints, fascia, and nerves respond to this postural crime scene?

Article Index

- Understanding Forward Neck Posture Anatomy

- The Effect of Head Weight on Upper Spine Load

- Muscle Tightness in the Upper Thoracic Region

- Thoracic Kyphosis from Chronic Neck Flexion

- Trapezius Strain and Mid-Back Tension

- Fascial Adhesions in Forward Head Posture

- Joint Compression and Limited Thoracic Movement

- Nerve Entrapment Caused by Poor Head Position

- Biomechanical Chain Reaction in the Spine

- Conclusion

Understanding Forward Neck Posture Anatomy

Forward neck posture, also called “text neck” or “nerd neck,” occurs when the head juts ahead of the shoulders rather than aligning neatly above them.

This misalignment shifts the body’s center of gravity forward, forcing the cervical and upper thoracic spine to bear unnatural loads.

Since the average adult head weighs 10–12 pounds, even a slight forward tilt can increase effective pressure on the neck up to 60 pounds, according to research from the journal Surgical Technology International.

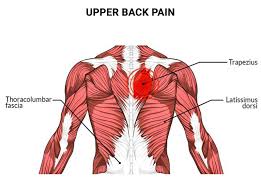

Over time, this added strain overstimulates the upper back muscles—especially the trapezius, rhomboids, and levator scapulae—leading to muscular fatigue, inflammation, and stiffness.

Joints and intervertebral discs also absorb extra stress, heightening the risk of cervical degeneration, disc herniation, and spinal misalignment.

From an anatomical perspective, a neutral head position maintains muscular balance and joint integrity.

But in a forward-leaning posture—often from prolonged screen use—the spine compensates awkwardly, kicking off a chronic cycle of tension, imbalance, and discomfort.

The Effect of Head Weight on Upper Spine Load

In a neutral posture, your head weighs a manageable 10–12 pounds—about the size of a bowling ball.

But shift it just one inch forward, and your neck and upper back are suddenly hauling the equivalent of a small dog.

At three inches?

That’s a 40-pound suitcase hanging off your spine like a poorly packed carry-on.

This is not just bad ergonomics—it is a muscular horror show. The upper thoracic muscles, especially the upper traps, rhomboids, and levator scapulae, go into overdrive trying to stabilize the head.

Imagine holding a heavy watermelon at arm’s length all day—you would cramp up, too. Over time, this chronic overload leads to micro-tears, reduced elasticity, and stiffness that makes turning your head feel like cranking a rusty gear.

So next time you are hunched over your phone, remember: your spine isn’t a coat rack for your head. Stack it straight, or your upper back will definitely start filing complaints.

Muscle Tightness in the Upper Thoracic Region

With forward neck posture, key muscles like the upper trapezius, levator scapulae, and semispinalis thoracis are thrown into a constant state of overwork.

But here is the twist—they are not just working harder, they are working wrong.

These muscles, which are designed for dynamic support and movement, become static shock absorbers for a misaligned head.

Instead of contracting and relaxing rhythmically, they tighten up like overtuned guitar strings just to keep the head from flopping forward.

Over time, this abnormal workload leads to serious muscular consequences. Muscle fibers start to develop fibrosis—where scar-like tissue replaces healthy muscle. This not only limits elasticity but also locks these muscles into a shortened, inflamed state.

The result? Reduced mobility, chronic upper back tightness, and that frustrating “knotty” feeling between the shoulder blades.

You might notice it creep in by mid-afternoon, especially if you have been glued to your TV screen all day. That burning tension across the upper back or stiffness near the base of your neck is not just fatigue—it is a cry for help from muscles that were never meant to carry your head like a misplaced backpack.

Without proper alignment, these tissues lose their functional harmony, and upper back discomfort becomes your new unwelcome coworker.

Thoracic Kyphosis from Chronic Neck Flexion

Here is how it takes shape:

- Compensatory Curvature Develops:

When the head drifts forward beyond its neutral position, the upper thoracic spine adapts by curving more than usual to counterbalance the shifted center of gravity. This excessive curvature is known as thoracic kyphosis. - Loss of Spinal Shock Absorption:

The natural S-shape of the spine is designed to absorb shocks and distribute loads efficiently. With thoracic kyphosis, the exaggerated curve flattens this S-curve, reducing the spine’s shock-absorbing capacity. The spine becomes more like a stiff rod than a spring. - Rib Cage Expansion Becomes Restricted:

A more hunched thoracic posture limits the rib cage’s ability to expand fully during breathing. This can result in shallower breaths, reduced lung capacity, and even chronic fatigue due to suboptimal oxygenation. - Posture Becomes Structurally “Locked In”:

Over time, what begins as a flexible postural adaptation becomes a permanent structural change. Muscles and ligaments adapt to the new shape, effectively locking the upper back into a rounded, rigid position. - Stiffness and Pain Increase with Movement:

As mobility is lost, daily movements like twisting, reaching, or stretching become limited and painful. This inflexibility often presents as chronic upper back stiffness, especially after long hours of sitting or working at a desk. - Long-Term Dysfunction Ensues:

Left uncorrected, thoracic kyphosis contributes to muscle imbalances, joint wear, and even nerve compression, setting the stage for long-term discomfort and spinal dysfunction.

Trapezius Strain and Mid-Back Tension

One of the first muscles to sound the alarm when forward neck posture sets in is the trapezius—a broad, triangular muscle that spans your upper back and shoulders.

In this misaligned posture, the upper trapezius becomes tight and overactive as it tries to hold the forward-leaning head aloft. Meanwhile, the middle and lower trapezius—responsible for stabilizing and retracting the shoulder blades—are left underused and overstretched.

This creates a perfect storm of muscular imbalance. The weakened lower sections can no longer anchor the scapulae (shoulder blades) efficiently, leading to poor shoulder mechanics, instability, and misfiring of surrounding muscles. As a result, your upper back enters a state of constant compensation.

The body responds by tightening other nearby muscles to ‘guard’ the area from further strain—like a neighborhood watch gone into overdrive.

This protective guarding may feel like persistent knots, tightness, or burning across the mid-back. And unfortunately, that upper back stiffness becomes your default setting—especially after long hours at a desk or behind a screen.

Fascial Adhesions in Forward Head Posture

Fascia is the body’s internal cling film—a web-like connective tissue that wraps around and through muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and joints, helping to support and organize them.

While it is naturally elastic and flexible, fascia is also highly responsive to posture. When you hold a forward neck posture for long periods—like when you are glued to your laptop or phone—the fascia starts to remodel itself to fit the muscle’s new static position.

This leads to fascial densification and adhesions, especially in the upper thoracic region. Adhesions are sticky spots where the fascia binds to underlying structures, while densification refers to thickening and loss of pliability.

Together, they create a feeling of tightness, restriction, or “stuckness” that doesn’t go away with a simple stretch.

Even when you attempt to move or extend your back, these fascial restrictions limit the gliding motion between layers of tissue, making your upper back feel stiff, tight, or uncooperative.

The longer the poor posture persists, the more entrenched and fibrotic these fascial changes become, further reinforcing dysfunctional movement patterns and chronic discomfort.

Joint Compression and Limited Thoracic Movement

Forward head posture isn’t just a muscular issue—it’s a mechanical one too. When your head creeps forward for hours on end, it doesn’t just burden the muscles; it places excessive pressure on the spinal joints, especially in the cervical and upper thoracic regions.

Forward head posture destabilizes your shoulder and causes unnecessary wear and tear.

Here’s how it affects your joints:

- Facet Joint Compression:

The facet joints, which guide spinal movement, become compressed as the head tilts forward. This “jamming” restricts mobility and causes stiffness in the neck and upper back. - Inflammation Builds Up:

Constant compression irritates the joint surfaces, leading to local inflammation, swelling, and a dull, aching discomfort in the upper spine. - Degenerative Changes Accelerate:

Over time, this mechanical overload contributes to premature joint wear-and-tear, including osteoarthritis, disc thinning, and bone spur formation. - Reduced Thoracic Rotation:

As the upper spine stiffens, your ability to twist or extend the thoracic region becomes limited—making movements like checking your rearview mirror feel like a full-body workout. - Persistent Stiffness:

That unrelenting “locked” feeling in your mid-back may actually be your facet joints crying out from prolonged compression—proof that posture problems run deeper than sore muscles.

Nerve Entrapment Caused by Poor Head Position

When your head plays the long game of leaning forward like it is chasing your phone, your spine pays the price—especially those tiny nerve doorways called intervertebral foramen.

These little openings allow spinal nerves to exit and communicate with the rest of your body.

But when the head chronically tilts forward, these gaps begin to narrow like a door slowly closing on a foot.

The result? Nerve impingement—particularly in the upper thoracic spine.

You might feel it as odd tingling down your arms, dull pain between your shoulder blades, or that mysterious stiffness that just would not quit, no matter how much you stretch or foam roll.

Even mild nerve irritation can send your body into protection mode. It is like your muscles call in a security lockdown: they tense up to guard the irritated area.

The upper back muscles contract defensively, trying to “brace” the nerve, but instead they end up creating a vicious feedback loop of tightness, discomfort, and frustration.

Your spine’s just trying to protect itself—but it sure feels like you’re stuck wearing a lead backpack.

Biomechanical Chain Reaction in the Spine

The spine is more than just a stack of vertebrae—it is a finely tuned kinetic chain where each segment affects the next, like dominoes in motion.

When the cervical spine (neck) leans forward, it kicks off a ripple effect that travels down through the thoracic spine and even into the lumbar region.

To counterbalance the weight shift, the upper thoracic spine often locks into a rigid extension, while the lower thoracic or lumbar segments may flex excessively to keep you upright. This compensatory see-saw throws your biomechanics out of whack.

As a result, certain muscles and joints—like the upper traps and thoracic extensors—get overused and over-fatigued, while others like the deep stabilizers go dormant. This muscle imbalance and joint overcompensation gradually rewires your movement patterns, making your upper back feel stiff, poorly coordinated, and perpetually “glued in place.”

It is not just poor posture—it is a full-body domino effect that starts with your neck and ends with an upper back that feels like it is made of concrete.

Conclusion

Forward head posture might start with an innocent chin jut during a Zoom call, but its impact snowballs fast—and it doesn’t stop at the neck.

It drags the upper back into a postural drama involving overworked muscles, jammed joints, restricted fascia, and cranky nerves. This is not just discomfort—it is a chronic biomechanical tug-of-war, where your upper back becomes the battlefield.

That nagging stiffness between your shoulder blades? It is not random—it is a direct response to the chaos above.

Massage guns, foam rollers, and chiropractic cracks may offer temporary relief, but they’re just slapping Band-Aids on a deeply rooted postural habit.

Unless you address the head-forward position, your upper back will keep returning to its tight, locked-in ways.

Understanding the “why” behind the stiffness empowers you to fix the “how.” It is not just bad luck—it is bad mechanics.

So next time you are leaning into your laptop like it owes you money, sit back and remember: your spine is not built for the slouch life.

Treat it right now, or it shall have its revenge in knots and crunches later.

References: