Head tilt, clinically referred to as torticollis, occurs when the head persistently tilts to one side due to an imbalance in neck muscles.

This condition can result from various factors, including injuries, neurological conditions, and muscular abnormalities.

However, inherited muscle imbalances, particularly in the neck and upper shoulder region, often play a significant role in the development of this postural deviation.

This article explores how and why inherited muscle imbalances lead to head tilt, discussing the genetic, anatomical, and neurological mechanisms involved, supported by scientific evidence and real-life examples.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Head Tilt and Muscle Imbalances

- Genetic Factors Behind Inherited Muscle Imbalances

- Anatomical Impact of Muscle Imbalances on Head Positioning

- Neurological Contributions to Head Tilt

- Developmental Aspects: The Role of Early Life

- Real-Life Examples of Head Tilt Caused by Inherited Imbalances

- FAQs on Forward Neck and Inherited Muscle Imbalance

- Conclusion

What is Head Tilt and Muscle Imbalances?

Head tilt can appear as a subtle inclination of the head or as a more pronounced misalignment.

It is often associated with an imbalance in neck muscles, particularly the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

These imbalances alter the natural equilibrium of the neck, leading to postural distortions.

While many cases of head tilt are attributed to environmental or acquired factors, inherited muscle imbalances remain an underlying cause for a significant number of individuals.

Inherited conditions, such as congenital muscular torticollis (CMT), illustrate the genetic predisposition to muscle imbalances that lead to head tilt.

These imbalances may manifest early in life, gradually worsening if left unaddressed.

Understanding the inherited aspect of muscle imbalances sheds light on why some individuals develop head tilt despite no apparent environmental triggers.

Genetic Factors Behind Inherited Muscle Imbalances

One of the most well-documented examples of an inherited condition that causes head tilt is congenital muscular torticollis (CMT).

This condition occurs when the sternocleidomastoid muscle on one side of the neck becomes shortened or tight, pulling the head toward the affected side and causing the chin to point in the opposite direction.

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), CMT is commonly diagnosed in infants and may result from a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental factors, such as restricted movement or positioning in the womb.

The genetic underpinnings of CMT often involve mutations or variations in genes responsible for muscle growth, elasticity, and repair.

For example, abnormalities in collagen-related genes can compromise the structural integrity of muscle fibers, making them more susceptible to imbalances. These genetic factors are frequently exacerbated by familial trends, as parents with similar muscle imbalances may pass down the condition to their children.

Studies, such as those highlighted by Kaplan et al. (2013), show that genetic mutations affecting muscle and connective tissue development can predispose individuals to conditions like CMT, creating a strong hereditary link.

Understanding the genetic basis of CMT underscores the importance of early diagnosis and targeted interventions to prevent long-term complications associated with head tilt.

Anatomical Impact of Muscle Imbalances on Head Positioning

Muscle imbalances can significantly disrupt the natural alignment of the head and neck by exerting uneven forces on the musculoskeletal system.

In conditions like congenital muscular torticollis (CMT), the shortened or tight sternocleidomastoid muscle on one side pulls the head toward the affected side, while the opposing muscles attempt to compensate but fail to restore balance.

This imbalance creates a cascade of compensatory postural adaptations, such as spinal curvature, elevated shoulders, and asymmetrical muscle development in the upper body.

Anatomical studies, including those reviewed in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (Kaplan et al., 2013), have shown that prolonged muscle imbalances can result in permanent structural changes in the cervical spine, including altered vertebral alignment, joint stiffness, and chronic muscle tension.

As per Best Forward Head Posture Fix research team, “These changes often exacerbate the tilt, leading to further discomfort, restricted range of motion, and functional limitations”.

Over time, untreated cases may become more severe, with the head tilt becoming more pronounced and potentially causing secondary conditions such as scoliosis or nerve compression.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing muscle imbalances early, as the progressive nature of structural adaptations can make correction more challenging and result in chronic pain and reduced quality of life as the individual ages.

Neurological Contributions to Head Tilt

The neurological system is integral to maintaining proper head posture, as it governs muscle coordination, tone, and balance through intricate neural pathways.

Disruptions in these pathways, whether due to genetic or acquired factors, can exacerbate inherited muscle imbalances, often contributing to conditions such as head tilt.

Neurological disorders like dystonia, characterized by involuntary and often sustained muscle contractions, can play a pivotal role in head positioning.

Cervical dystonia, in particular, presents as abnormal postures or repetitive movements of the neck and head, further complicating preexisting muscular asymmetries.

Dystonia is frequently linked to dysfunction within the basal ganglia, a key brain region responsible for regulating motor control and muscle tone.

Research published in The Lancet Neurology (Klein et al., 2014) underscores the genetic foundations of cervical dystonia, highlighting inherited mutations in genes such as TOR1A.

These genetic abnormalities impair neural signaling, disrupting the fine-tuned control of muscular activity.

When preexisting muscle imbalances, such as those associated with congenital muscular torticollis, coexist with neurological deficits, a feedback loop may develop.

This loop perpetuates abnormal head postures and amplifies the severity of the tilt over time, underscoring the interconnected nature of musculoskeletal and neurological factors in maintaining postural alignment.

These findings illuminate the complex interplay between inherited neurological and muscular contributors to head tilt.

Developmental Aspects: The Role of Early Life

Inherited muscle imbalances often manifest during infancy or early childhood, making early detection crucial for effective intervention.

Congenital muscular torticollis, for instance, is often identified within the first few weeks of life. The condition may result from in-utero positioning, where the baby’s head remains tilted due to restricted movement, or from genetic predispositions affecting muscle elasticity.

A study by the Stanford Children’s Health team (2018) highlights the long-term consequences of untreated CMT, including facial asymmetry, developmental delays, and compensatory scoliosis.

Infants with untreated muscle imbalances may struggle to achieve developmental milestones such as crawling or sitting upright, further compounding the problem.

Early intervention, such as physical therapy focusing on stretching and strengthening the affected muscles, has proven highly effective.

According to the Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine (Ohman et al., 2016), 90% of infants treated within the first six months of life show significant improvement, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and management.

Real-Life Examples of Head Tilt Caused by Inherited Imbalances

Let us walk you through 2 such examples:

Case 1: Emma, the Infant with Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT)

Emma’s journey began when her parents noticed something unusual during her first few weeks of life.

Her head seemed to consistently tilt to the right, and attempts to reposition her didn’t work.

Concerned, they visited a pediatrician, who diagnosed Emma with congenital muscular torticollis (CMT), a condition caused by a shortened sternocleidomastoid muscle on one side of her neck.

While the diagnosis was alarming, Emma’s story took a positive turn thanks to early intervention.

The pediatrician referred Emma to a physical therapist specializing in infant conditions. Therapy involved gentle stretching exercises to lengthen the tight muscle and positional adjustments during sleep and feeding to encourage balanced neck movement.

Her parents also diligently practiced the recommended exercises at home, turning playtime into therapy sessions. By her first birthday, Emma’s posture was indistinguishable from any other child her age.

Her recovery highlights how early diagnosis and intervention can lead to complete resolution of inherited muscle imbalances.

Case 2: John, the Adult with Untreated Muscle Imbalance

Unlike Emma, John’s story is one of missed opportunities.

As a child, John’s parents noticed his head tilting slightly to one side, but they assumed he would “grow out of it.” Unfortunately, the untreated muscle imbalance followed him into adulthood.

By the time John reached his mid-thirties, the tilt had caused secondary complications, including chronic neck pain, spinal misalignment, and tension headaches that disrupted his daily life.

Seeking relief, John began physical therapy, which included strengthening and stretching exercises along with ergonomic adjustments at work.

While these measures alleviated some discomfort, his head tilt persisted due to the long-standing adaptations his body had made over the years.

John’s experience underscores the critical importance of addressing inherited muscle imbalances early, as untreated cases can lead to lifelong challenges and only partial improvement later in life.

His story serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of delaying treatment.

FAQs on Forward Neck and Inherited Muscle Imbalance

A quick look at the top 5 FAQs on forward head posture caused by inherited muscle imbalances:

Can Forward Head Posture Be Inherited From Parents?

Yes, to a certain extent. While posture is heavily influenced by lifestyle and environment, genetics can play a role in predisposing certain muscle imbalances that contribute to forward head posture (FHP).

If a parent has a naturally tight pectoral structure, a short neck, or a tendency for thoracic spine rounding, their child may inherit similar anatomical traits.

These inherited traits do not guarantee FHP, but they create a biomechanical framework where the risk is higher—especially when compounded by poor posture habits like excessive screen time or sedentary behavior.

What Muscle Imbalances Are Commonly Inherited And Linked To Forward Head Posture?

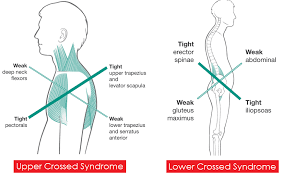

The most common inherited imbalances include:

- Overactive sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius muscles, which pull the head forward and upward.

- Underactive deep neck flexors that fail to stabilize the cervical spine.

- Tight chest muscles (pectoralis major and minor) combined with weak rhomboids and lower traps.

These muscular patterns can be influenced by genetics. For instance, someone born with a naturally kyphotic (rounded) upper spine might experience chest tightening and forward neck displacement more quickly than someone with a more neutral spinal structure.

How Can I Tell If My Forward Head Posture Is Due To Inherited Muscle Imbalances?

Look for a family pattern. If multiple members of your family show signs of slouched shoulders, protruding heads, or chronic neck stiffness, it could indicate an inherited predisposition.

However, a postural assessment by a physiotherapist is the most reliable way to determine if genetics are a factor. They can evaluate your skeletal alignment and muscle activation to identify whether your posture problems are congenital or developed from habit.

Can Inherited Muscle Imbalances Be Corrected Or Improved?

Absolutely. Even if muscle imbalances are inherited, they are not irreversible. Targeted corrective exercises like chin tucks, wall angels, scapular squeezes, and deep neck flexor training can rebalance the system.

Stretching the overactive muscles and strengthening the underused ones helps correct faulty alignment. It may take longer if your imbalances are genetic, but consistent, focused work can create lasting improvements.

Should Children With A Family History Of FHP Be Monitored?

Yes, early awareness can be a game-changer. If FHP runs in the family, it is wise to monitor a child’s postural development during growth spurts, particularly during tech-heavy teenage years.

Introducing ergonomic setups, posture-friendly backpacks, and simple neck-strengthening routines can prevent the inherited predisposition from becoming a long-term postural defect.

Takeaway

Inherited muscle imbalances, particularly in conditions like congenital muscular torticollis, significantly contribute to head tilt by disrupting the natural alignment of the neck and head.

These imbalances arise from a combination of genetic, anatomical, and neurological factors, often manifesting early in life.

While the severity and impact of head tilt can vary, the importance of early diagnosis and intervention cannot be overstated.

Studies have consistently shown that timely physical therapy and appropriate management strategies can mitigate the long-term consequences of these inherited imbalances, improving both posture and quality of life.

Recognizing the genetic and developmental underpinnings of head tilt is essential for addressing the condition effectively.

References: