Neck strain is rarely just “tight muscles.” For many people, the culprits are tiny, hyper-irritable spots inside a taut band of muscle called myofascial trigger points.

Pressing them can feel exquisitely tender and may even reproduce the familiar headache behind your eye or the ache that crawls down your shoulder blade.

Trigger point therapy aims to calm those hot spots so the whole muscle can relax, circulate, and move again.

In this guide, Best Forward Head Posture Fix research staff would unpack what trigger points are, why they aggravate necks, what the research says about massage, ischemic compression, and dry needling, and how to combine hands-on care with posture tweaks so relief actually lasts.

By the end, you would have a practical plan (and realistic expectations) for using trigger point therapy to get your neck feeling like, well, your neck again.

Article Index

- What Exactly Are Trigger Points?

- Why Trigger Points Stir Up Neck Strain (and Referred Pain)

- The Big Four: Upper Trapezius, Levator Scapulae, SCM, Suboccipitals

- How Trigger Point Therapy Works (Techniques and What to Expect)

- What the Evidence Says (Wins, Limits, and Best Bets)

- At-Home Care: A Safe, Simple Routine

- When to Seek Professional Help (and Red Flags)

- Putting It All Together: Your Neck-Friendly Action Plan

What Exactly Are Trigger Points?

A trigger point is a hypersensitive spot in a taut band of muscle that hurts when pressed and can send pain to a distant area, known as referred pain.

An international pain-medicine consensus highlights three main diagnostic features: a taut band, a tender nodule, and referred pain elicited by palpation.

These criteria help clinicians distinguish everyday stiffness from myofascial pain that benefits from targeted treatment.

From a patient’s perspective, this is why a small knot in your upper trapezius can make reading at a desk miserable, or why a point in your neck can trigger a temple or tension headache.

While researchers still debate the exact mechanisms, most agree that motor end-plate dysfunction, reduced blood flow, and sensitized nerve endings maintain the cycle of pain and muscle guarding—until we intervene.

Recent reviews emphasize using a cluster of signs rather than just one, and treating the muscle as a functional unit rather than chasing isolated spots.

Why Trigger Points Stir Up Neck Strain? (and Referred Pain)

Trigger points do not just hurt locally—they project pain in predictable maps.

In the neck, this often means pain to the back of the head, around the eye, into the jaw, or down the shoulder blade. That’s why pressing on a knot can “light up” a familiar pattern.

Clinical studies show that compressing active trigger points reliably reproduces patients’ typical pain.

Functionally, these points shorten the muscle, restrict range of motion, and load neighboring joints, creating the day-to-day “stiff neck” spiral.

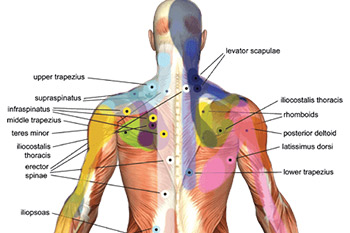

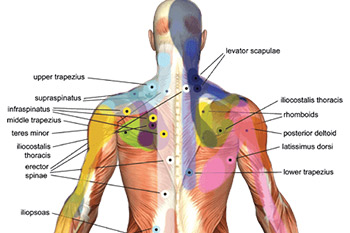

The Big Four: Upper Trapezius, Levator Scapulae, SCM, Suboccipitals

- Upper Trapezius (UT)

The most common neck trigger point site. UT points can send pain up the neck and to the side of the head; they often flare with prolonged desk work or shoulder hiking. - Levator Scapulae

Trigger points here are tucked deep to the trapezius, often referring pain along the inner edge of the shoulder blade and up the back of the neck—especially noticeable when checking blind spots while driving. - Sternocleidomastoid (SCM)

These points can be sneaky: they may refer pain to the temple, ear, eyebrow, or behind the eye, and sometimes come with dizziness or a sense of ear fullness. - Suboccipitals

Small muscles at the base of the skull that, when irritated, can provoke band-like occipital headaches and neck stiffness. They often co-activate with UT and levator scapulae points in headache populations.

As you read research or instructions online, you would often see phrases like myofascial trigger points in the neck and shoulders—a reminder that these muscles group together functionally during posture and screen time.

How Trigger Point Therapy Works? (Techniques and What to Expect)

Ischemic compression (sustained pressure):

A therapist or tool applies tolerable pressure (mild–moderate tenderness) directly on the point for 30–90 seconds.

The goal is to temporarily limit blood flow and then allow it to return, normalizing tone and sensitivity.

Clinical trials in neck pain show immediate pain reduction and better pressure-pain thresholds after sessions targeting UT points.

Manual Trigger Point Techniques:

These include pressure-release, muscle energy technique, and strain-counterstrain.

Evidence shows short-term improvements in pain and range, especially when paired with stretching or exercise.

Dry Needling and Injections:

- Dry needling uses thin needles to provoke a local twitch and desensitize the point. Reviews suggest short-term pain reduction, sometimes comparable to manual compression.

- Trigger point injections with local anesthetic can help some patients, though results are mixed long term. They tend to work best when combined with active rehab.

Myofascial Release and Massage:

Massage can modulate pain and improve tolerance. Reviews suggest that more frequent sessions (for example, eight sessions over four weeks) are more effective than occasional treatments.

Self-myofascial release (SMR):

Foam rollers, balls, and gentle tools can reduce perceived tightness and improve motion in the short term. Softer implements are often more comfortable and effective than very hard balls.

What the Evidence Says? (Wins, Limits, and Best Bets)

- Ischemic compression is consistently effective on upper trapezius trigger points, producing immediate relief.

- Dry needling can reduce pain short-term, with injections sometimes offering stronger initial results.

- Manual therapies show improvements but work best when paired with stretching or strengthening exercises.

- Massage is helpful when delivered in enough sessions and combined with other strategies.

- Diagnosis should be based on a cluster of features rather than a single sign to improve accuracy and results.

At-Home Care: A Safe, Simple Routine

Here is a practical, gentle routine you can try at home:

Tools: a soft ball or medium-density foam roller.

- Step 1: Scan your neck and shoulders while breathing deeply.

- Step 2: Apply pressure to a tender spot at about 5–6 out of 10 discomfort for 30–45 seconds.

- Step 3: After pressure, perform gentle side-bends and rotations.

- Step 4: Reinforce with scapular retractions and chin-tuck isometrics.

- Step 5: Adjust ergonomics—keep your screen at eye level, elbows close, and take movement breaks.

If you are exploring self-massage for neck trigger points, think little and often instead of intense pressure.

When to Seek Professional Help? (and Red Flags)

Seek medical advice if you experience trauma, unexplained fever or weight loss, night pain that does not improve with rest, neurological symptoms like numbness or weakness, or severe headaches.

A physical therapist can help determine whether techniques like ischemic compression for cervical myofascial pain, dry needling for trapezius trigger points, or structured exercise are right for you.

Putting It All Together: Your Neck-Friendly Action Plan

- Learn your pattern. Desk workers often have UT and levator scapulae points; some also experience sternocleidomastoid trigger point symptoms with facial discomfort.

- Start with pressure and movement. Combine pressure with gentle motion, then follow with strengthening.

- Be consistent. Frequent shorter sessions are better than occasional intense treatments.

- Seek professional options if needed. If self-care isn’t enough, explore dry needling or injections alongside rehab.

- Maintain gains. Use posture, strength training, and breaks to keep muscles balanced.

Conclusion: A Practical Solution that Sticks

Trigger point therapy helps neck strain by desensitizing irritable muscle spots, restoring normal tone, and widening pain-free movement.

The best results come from an integrated plan: targeted pressure on the right points, immediate gentle movement, and consistent strengthening and posture work.

Evidence supports ischemic compression and dry needling for short-term relief, while massage and myofascial release work better with regular sessions and exercise.

The practical solution is simple: identify your trigger points, apply focused therapy, reinforce with movement, and adjust your daily habits.

This way, trigger point therapy for neck pain relief becomes more than a quick fix—it is a sustainable path to a healthier, more comfortable neck.

References: